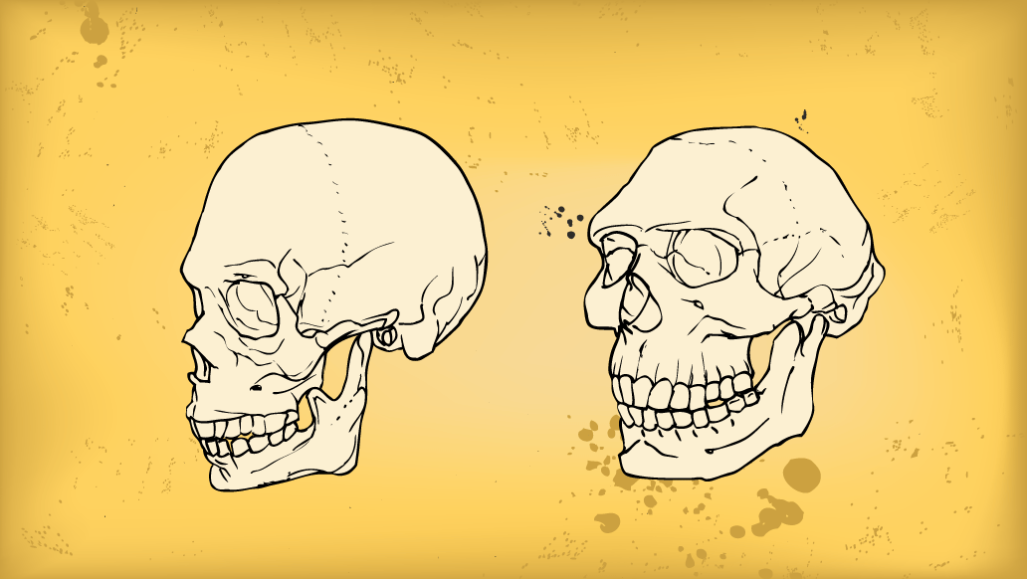

Domestic animals’ cuteness and humans’ relatively flat faces may be the work of a gene that controls some important developmental cells, a study of lab-grown human cells suggests. Some believe that humans domesticated themselves over many generations, by weeding out certain traits. As people supposedly selected among themselves for tameness traits, other genetic changes occurred that resulted in humans, like other domesticated animals, having a different appearance than their predecessors. Human faces are smaller, flatter and have less prominent brow ridges than Neandertal faces did, for instance.

Some studies have suggested that differences in some genes implicated in neural crest cell function might have been important in the domestication of cats, horses and other animals. But none of those studies explained how those genetic differences led to altered behaviors or looks between wild and domesticated animals.

In a new study, researchers studied cells from people with developmental disorders to learn more about neural crest cells. One gene, BAZ1B, controls 40 percent of genes active in those cells. Altering levels of BAZ1B’s protein affects how quickly neural crest cells move in lab tests, the scientists report December 4 in Science Advances.

Researchers found that genes under BAZ1B’s direction are among those that changed both in animals during domestication and in modern humans as they evolved. Some variants of those genes are found in nearly every modern human, but either weren’t found or were not as prevalent in the DNA of their extinct Neandertal or Denisovan cousins, according to the researchers.

The team needed to know whether altering amounts of the BAZ1B protein had any effect on neural crest cells. So the researchers reprogrammed skin cells from people with Williams or the duplication syndrome into stem cells. The scientists then grew the stem cells into neural crest cells. For comparison, the team also made neural crest cells from people who develop normally and who have the usual two copies of BAZ1B and other 27 genes. Also included were cells from a person with a mild form of Williams syndrome. That person was missing many of the genes in the region, but still had two copies of BAZ1B.

When researchers reduced these protein levels in each of the different types of cells, the neural crest cells moved slower. Other genes’ activities were also influenced by the dose of BAZ1B and its protein in cells, the researchers found. "Those results correlating the amount of BAZ1B protein with cellular biology is exactly what would be expected if a neural crest cell gene were responsible for domestication syndrome," says Adam Wilkins, an evolutionary biologist.

No comments:

Post a Comment